Everything about pads

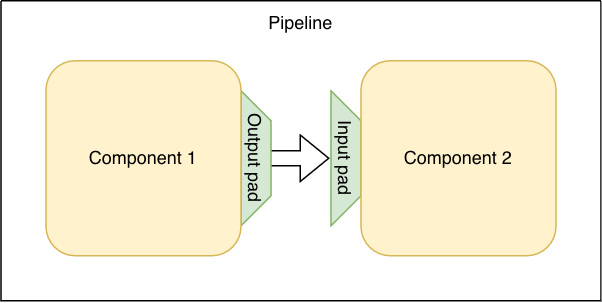

View SourceWhen developing intuition about the structure of pipelines, pads are something that can't be ignored. If you think about elements and bins (from now on collectively referred to as components) as some sort of containers or boxes in which processing happens, then pads are the parts that these containers are connected with.

There are some constraints regarding pads:

- A pad of one component can only connect to a single pad of another component. Only once these two pads are linked, communication through them can happen.

- One pad needs to be an input pad, and the other an output pad.

- The accepted formats of the pads need to match - stream formats passing between elements through these pads need to match the accepted formats of both.

When looking at the insides of components, the pads are their main way to

communicate with other components in the pipeline. There are four types

of information that can be exchanged between components through pads -

stream formats,

events, buffers and

:end_of_streams.

When a component receives information of one of these types from another one, it

receives it on a pad. The reference to this pad is then also available as an argument

of the callback that handles the received information. For example, an invocation

of a handle_buffer/4

callback would mean that a buffer buffer has arrived on a pad some_pad:

@impl true

def handle_buffer(some_pad, buffer, context, state) do

... ^^^^^^^^

endWhen a component wants to send information to another

component in the pipeline, it should send it on a pad that's linked to it. It

can do that by using the pad reference in actions that send these types of

information, for example returning a

:buffer action

from a callback would mean that a buffer buffer will be sent on a pad some_pad:

@impl true

def handle_something(..., _context, state) do

...

{[buffer: {some_pad, buffer}], state}

end ^^^^^^^^Defining pads

To define what pads a component will have and how they'll behave, we use

def_input_pad/2

and def_output_pad/2 macros.

Input pads can only be defined for Bins, Sinks, Filters and Endpoints, and output

pads can only be defined for Bins, Sources, Filters and Endpoints.

The first argument for these macros is a name, which will then be used to

identify the pads. The second argument is a pad spec

keyword list, which is used to define how this pad will work. An option we'll

now focus on is availability, which

determines if the pad is static or dynamic.

Static pads

Static pads are pretty straightforward - when a static pad is defined there will always be exactly one instance of this pad and it's referenced by its name.

File Source Example

An example of an element with only static pads is a File Source.

This element reads the contents of a file and sends them in batches through a static

output pad. The content of the buffers sent by this element is unknown - the file

that's being read can contain anything - so this pad has :accepted_format set to

%RemoteStream{type: :bytestream}. That means that any stream format that

matches on this struct can be sent on the output pad and this fact has to be

accounted for when linking a component after the source.

A pipeline spec with a file source passing buffers to an MP4 demuxer could look like this:

@impl true

def handle_init(_context, state) do

spec =

child(:source, %Membrane.File.Source{location: "my_file.mp4"})

|> via_out(:output)

|> via_in(:input)

|> child(:mp4_demuxer, Membrane.MP4.ISOM.Demuxer)

{[spec: spec], state}

endThis spec will link a pad named :output of the source to a pad named

:input of the demuxer. However, this can be shortened - if an output pad is

called :output or an input pad is called :input, their respective

via_in/3 and

via_out/3 calls can be omitted and

Membrane will automatically recognize and link them:

@impl true

def handle_init(_context, state) do

spec =

child(:source, %Membrane.File.Source{location: "my_file.mp4"})

|> child(:mp4_demuxer, Membrane.MP4.ISOM.Demuxer)

{[spec: spec], state}

endDynamic pads

Dynamic pads are a bit more complex. They're used when the number of pads of a

given type is variable - dependent on the processed stream or external factors.

The creation of these pads is controlled by the parent of the component - if a

:spec action linking the dynamic pad is

being executed, then the pad is created dynamically and the component needs to

handle this, in most cases with

handle_pad_added/3. This

callback is called only for dynamic pads.

Another thing that's different is the way the pad are referenced. The pad's name

can't just be used as the pad's reference, because it wouldn't be unique.

Dynamic pads are identified by Pad.ref/2, which takes

the pad's name and some unique reference as arguments. The result is a unique

pad reference that is also associated with a given pad's specification through

its name. When a new pad is linked, its reference is made known to the element

through the first argument of

handle_pad_added/3.

MP4 Demuxer Example

An example of an element using dynamic pads is an MP4 Demuxer. This element has an input pad, from which it receives the contents of an MP4 container, and output pads, on which it'll send the different tracks that were in the container. The input pad can be static, however MP4 containers can have different numbers and kinds of tracks, so the output pad needs to be dynamic.

We'll consider the case when we don't have any prior information about the

tracks in this MP4 container. Because of this, the parent pipeline or bin of this

demuxer won't initially know how many pads should be linked. To solve this

problem, the demuxer will identify the tracks in the incoming stream and send a

message to its parent in the form of

{:new_tracks, [{track_id :: integer(), content :: struct()}]}.

The list consists of tuples corresponding to tracks, where the first

element is a track id and will be used to identify the corresponding pad,

and the second is a stream format contained in the track.

Initially, the parent will only create the elements before and including the demuxer:

@impl true

def handle_init(_context, state) do

spec =

child(:source, %Membrane.File.Source{location: "my_file.mp4"})

|> child(:mp4_demuxer, Membrane.MP4.ISOM.Demuxer)

{[spec: spec], state}

endThe source will start providing the demuxer with the MP4 container content, from which the demuxer will identify tracks and notify its parent about them. The parent now has to link an output pad of the demuxer for each track received, which can look like this:

@impl true

def handle_child_notification({:new_tracks, tracks}, :mp4_demuxer, _context, state) do

spec =

Enum.map(tracks, fn {id, format} ->

get_child(:mp4_demuxer)

|> via_out(Pad.ref(:output, id))

|> ...

end)

{[spec: spec], state}

endThe elements that the output pads will be linked to should be based on what stream

format is in the format variable - different formats require different approaches.

After this spec is returned, the demuxer will now have the

handle_pad_added/3 callback

called for each new linked pad:

@impl true

def handle_pad_added(Pad.ref(:output, track_id), _context, state) do

...

endIt will now know that these pads are linked and ready to pass buffers forward.

An operation that's less common than linking dynamic pads, but also important,

is unlinking them. If the parent removed a child with

t:remove_children/0 action:

@impl true

def handle_something(..., _context, state) do

...

{[remove_children: :some_child], state}

endThen the child with name :some_child would be stopped and removed from the

pipeline, unlinking all its pads. If an input pad of this child happened to be

connected to our demuxer, then the

handle_pad_removed/3

would be called in the demuxer with a reference to the pad that was unlinked:

@impl true

def handle_pad_removed(Pad.ref(:output, unlinked_track_id), _context, state) do

...

endThe demuxer should react to this information accordingly, for example it should now know that it can no longer send buffers on this pad, because it has been unlinked and essentially no longer exists.

If a link has dynamic pads on both sides, the parent could also return a

:remove_link action,

which would only remove the link, resulting in

handle_pad_removed/3

being called in children on both sides of it.

Life cycle of a pad

The life cycle of components is explored more broadly in this guide. Here, we'll take a closer look at the life cycle of a pad, mostly focusing on elements.

Creation

Static pads are essentially created and linked at the same time as the whole component and exist alongside it for its entire lifespan - they have to be linked at the same time the component is created.

Dynamic pads can be linked and unlinked throughout their components' lifespan.

There can also be multiple instances of a dynamic pad.

Because of this, each creation can be handled separately in

handle_pad_added/3 callback,

which is called every time a new dynamic pad is linked, and therefore

created.

Playback

When an element is in :stopped

playback, nothing can be sent on its pads - the

pipeline is not ready. Only when an element enters :playing playback and

handle_playing/2 callback is

called can it assume that the pipeline is ready for communication and can

send on and receive information from its pads.

Removal

Static pads are removed and unlinked only once their component is terminated.

Dynamic pads can be removed during the lifespan of their component. For each removal

a handle_pad_removed/3

callback is called.

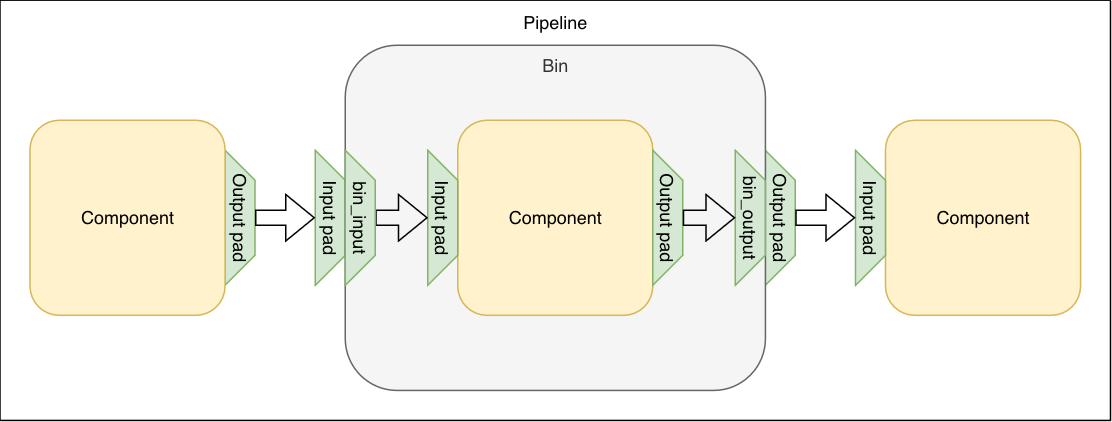

Pads in bins

We know that when it comes to linking pads between components, bins behave just like elements. However, when we take a look inside them, they are pretty different. While elements can interact with information moving through their pads directly with callbacks, bins are only containers for other components. They don't interact with information moving through their pads directly, they forward it to components inside them.

The insides of a bin can be thought of as a pipeline of sorts. The components

are created with the :spec action and the

bin is their parent. The way that these components can send and receive

information on the bin's pads is by linking with

bin_input and

bin_output. These functions can be

thought of as the "interior" part of the bin's pad.

For example, if a bin has

a dynamic input pad called :input, and a single static output pad called :output,

it can behave like this:

@impl true

def handle_setup(_ctx, state) do

spec =

child(:comp, SomeComponent)

|> bin_output(:output)

{[spec: spec], state}

endWhen the bin is being set up, it creates a SomeComponent child named :comp,

which connects its output pad to the bin_output corresponding to the bin's

:output pad. Now whenever this child sends or receives something on its output

pad, it's received by or sent to whatever component is connected to the bin's

:output pad.

@impl true

def handle_pad_added(Pad.ref(:input, id) = pad, _ctx, state) do

spec =

bin_input(pad)

|> child(SomeOtherComponent)

|> get_child(:comp)

{[spec: spec], state}

endEvery time a new input pad of the bin is created, the

handle_pad_added/3 callback is called.

The bin has to connect this pad to something within a 5-second timeout,

otherwise a LinkError will be

raised. A new SomeOtherComponent child is created and its input pad is

connected to a bin_input corresponding to the newly created pad. Now whenever

this child sends or receives something on its input pad, it's received by or

sent to whatever component is connected to the bin's newly created pad.

It's worth noting that pads of bins are only an abstraction. When a component links with a bin, it actually links directly to one of the components inside of it to avoid unnecessary forwarding of messages.