Adding Pages

Our task for this guide is to add two new pages to our Phoenix project. One will be a purely static page, and the other will take part of the path from the URL as input and pass it through to a template for display. Along the way, we will gain familiarity with the basic components of a Phoenix project: the router, controllers, views, and templates.

When Phoenix generates a new application for us, it builds a top-level directory structure like this:

├── _build

├── assets

├── config

├── deps

├── lib

│ └── hello

│ └── hello_web

│ └── hello.ex

│ └── hello_web.ex

├── priv

├── testMost of our work in this guide will be in the lib/hello_web directory, which holds the web-related parts of our application. It looks like this when expanded:

├── channels

│ └── user_socket.ex

├── controllers

│ └── page_controller.ex

├── templates

│ ├── layout

│ │ └── app.html.eex

│ └── page

│ └── index.html.eex

└── views

│ ├── error_helpers.ex

│ ├── error_view.ex

│ ├── layout_view.ex

│ └── page_view.ex

├── endpoint.ex

├── gettext.ex

├── router.exAll of the files which are currently in the controllers, templates, and views directories are there to create the “Welcome to Phoenix!” page we saw in the last guide. We will see how we can re-use some of that code shortly. When running in development, code changes will be automatically recompiled on new web requests.

All of our application’s static assets like js, css, and image files live in assets, which are built into priv/static by brunch or other front-end build tools. We won’t be making any changes here for now, but it is good to know where to look for future reference.

├── assets

│ ├── css

│ │ └── app.css

│ ├── js

│ │ └── app.js

│ └── static

│ └── node_modules

│ └── vendorThere are also non web-related files we should know about. Our application file (which starts our Elixir application and its supervision tree) is at lib/hello/application.ex. We also have our Ecto Repo in lib/hello/repo.ex for interacting with the database. We’ll touch on Ecto in an upcoming guide.

lib

├── hello

| ├── application.ex

| └── repo.ex

├── hello_web

| ├── channels

| ├── controllers

| ├── templates

| ├── views

| ├── endpoint.ex

| ├── gettext.ex

| └── router.exOur lib/hello_web directory contains web-related files – routers, controllers, templates, channels, etc. The rest of our greater Elixir application lives inside lib/hello, and you structure code here like any other Elixir application.

Enough prep, let’s get on with our first new Phoenix page!

A New Route

Routes map unique HTTP verb/path pairs to controller/action pairs which will handle them. Phoenix generates a router file for us in new applications at lib/hello_web/router.ex. This is where we will be working for this section.

The route for our “Welcome to Phoenix!” page from the previous Up And Running Guide looks like this.

get "/", PageController, :indexLet’s digest what this route is telling us. Visiting http://localhost:4000/ issues an HTTP GET request to the root path. All requests like this will be handled by the index function in the HelloWeb.PageController module defined in lib/hello_web/controllers/page_controller.ex.

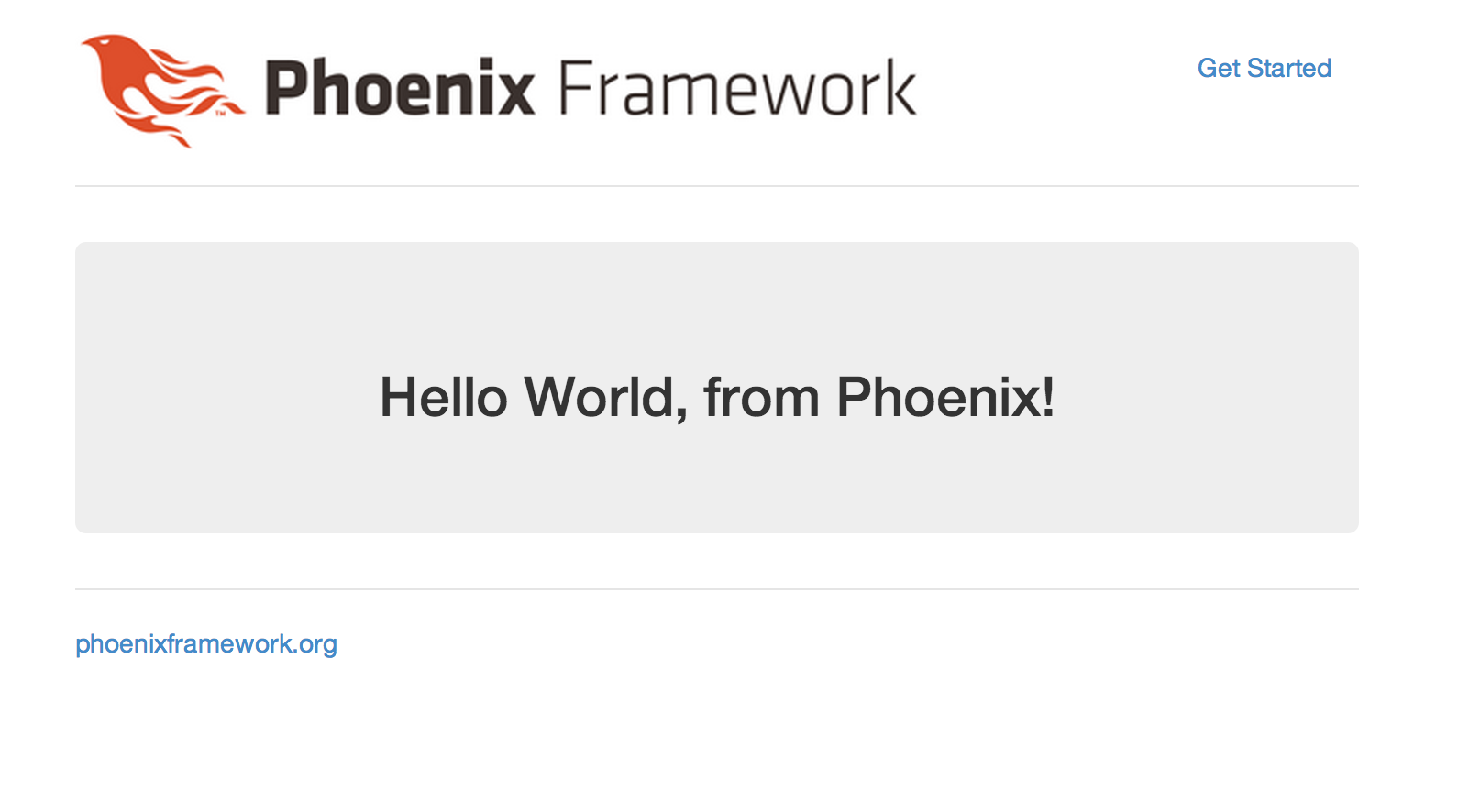

The page we are going to build will simply say “Hello World, from Phoenix!” when we point our browser to http://localhost:4000/hello.

The first thing we need to do to create that page is define a route for it. Let’s open up lib/hello_web/router.ex in a text editor. It should currently look like this:

defmodule HelloWeb.Router do

use HelloWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_flash

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

pipeline :api do

plug :accepts, ["json"]

end

scope "/", HelloWeb do

pipe_through :browser # Use the default browser stack

get "/", PageController, :index

end

# Other scopes may use custom stacks.

# scope "/api", HelloWeb do

# pipe_through :api

# end

end

For now, we’ll ignore the pipelines and the use of scope here and just focus on adding a route. (We cover these topics in the Routing Guide, if you’re curious.)

Let’s add a new route to the router that maps a GET request for /hello to the index action of a soon-to-be-created HelloWeb.HelloController:

get "/hello", HelloController, :indexThe scope "/" block of our router.ex file should now look like this:

scope "/", HelloWeb do

pipe_through :browser # Use the default browser stack

get "/", PageController, :index

get "/hello", HelloController, :index

endA New Controller

Controllers are Elixir modules, and actions are Elixir functions defined in them. The purpose of actions is to gather any data and perform any tasks needed for rendering. Our route specifies that we need a HelloWeb.HelloController module with an index/2 action.

To make that happen, let’s create a new lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_controller.ex file, and make it look like the following:

defmodule HelloWeb.HelloController do

use HelloWeb, :controller

def index(conn, _params) do

render conn, "index.html"

end

endWe’ll save a discussion of use HelloWeb, :controller for the Controllers Guide. For now, let’s focus on the index/2 action.

All controller actions take two arguments. The first is conn, a struct which holds a ton of data about the request. The second is params, which are the request parameters. Here, we are not using params, and we avoid compiler warnings by adding the leading _.

The core of this action is render conn, "index.html". This tells Phoenix to find a template called index.html.eex and render it. Phoenix will look for the template in a directory named after our controller, so lib/hello_web/templates/hello.

Note: Using an atom as the template name will also work here,

render conn, :index, but the template will be chosen based off the Accept headers, e.g."index.html"or"index.json".

The modules responsible for rendering are views, and we’ll make a new one of those next.

A New View

Phoenix views have several important jobs. They render templates. They also act as a presentation layer for raw data from the controller, preparing it for use in a template. Functions which perform this transformation should go in a view.

As an example, say we have a data structure which represents a user with a first_name field and a last_name field, and in a template, we want to show the user’s full name. We could write code in the template to merge those fields into a full name, but the better approach is to write a function in the view to do it for us, then call that function in the template. The result is a cleaner and more legible template.

In order to render any templates for our HelloController, we need a HelloView. The names are significant here - the first part of the names of the view and controller must match. Let’s create an empty one for now, and leave a more detailed description of views for later. Create lib/hello_web/views/hello_view.ex and make it look like this:

defmodule HelloWeb.HelloView do

use HelloWeb, :view

endA New Template

Phoenix templates are just that, templates into which data can be rendered. The standard templating engine Phoenix uses is EEx, which stands for Embedded Elixir. Phoenix enhances EEx to include automatic escaping of values. This protects you from security vulnerabilities like Cross-Site-Scripting with no extra work on your part. All of our template files will have the .eex file extension.

Templates are scoped to a view, which are scoped to controller. Phoenix creates a lib/hello_web/templates directory where we can put all these. It is best to namespace these for organization, so for our hello page, that means we need to create a hello directory under lib/hello_web/templates and then create an index.html.eex file within it.

Let’s do that now. Create lib/hello_web/templates/hello/index.html.eex and make it look like this:

<div class="jumbotron">

<h2>Hello World, from Phoenix!</h2>

</div>Now that we’ve got the route, controller, view, and template, we should be able to point our browsers at http://localhost:4000/hello and see our greeting from Phoenix! (In case you stopped the server along the way, the task to restart it is mix phx.server.)

There are a couple of interesting things to notice about what we just did. We didn’t need to stop and re-start the server while we made these changes. Yes, Phoenix has hot code reloading! Also, even though our index.html.eex file consisted of only a single div tag, the page we get is a full HTML document. Our index template is rendered into the application layout - lib/hello_web/templates/layout/app.html.eex. If you open it, you’ll see a line that looks like this:

<%= render @view_module, @view_template, assigns %>which is what renders our template into the layout before the HTML is sent off to the browser.

Another New Page

Let’s add just a little complexity to our application. We’re going to add a new page that will recognize a piece of the URL, label it as a “messenger” and pass it through the controller into the template so our messenger can say hello.

As we did last time, the first thing we’ll do is create a new route.

A New Route

For this exercise, we’re going to re-use the HelloController we just created and just add a new show action. We’ll add a line just below our last route, like this:

scope "/", HelloWeb do

pipe_through :browser # Use the default browser stack.

get "/", PageController, :index

get "/hello", HelloController, :index

get "/hello/:messenger", HelloController, :show

endNotice that we put the atom :messenger in the path. Phoenix will take whatever value that appears in that position in the URL and pass a Map with the key messenger pointing to that value to the controller.

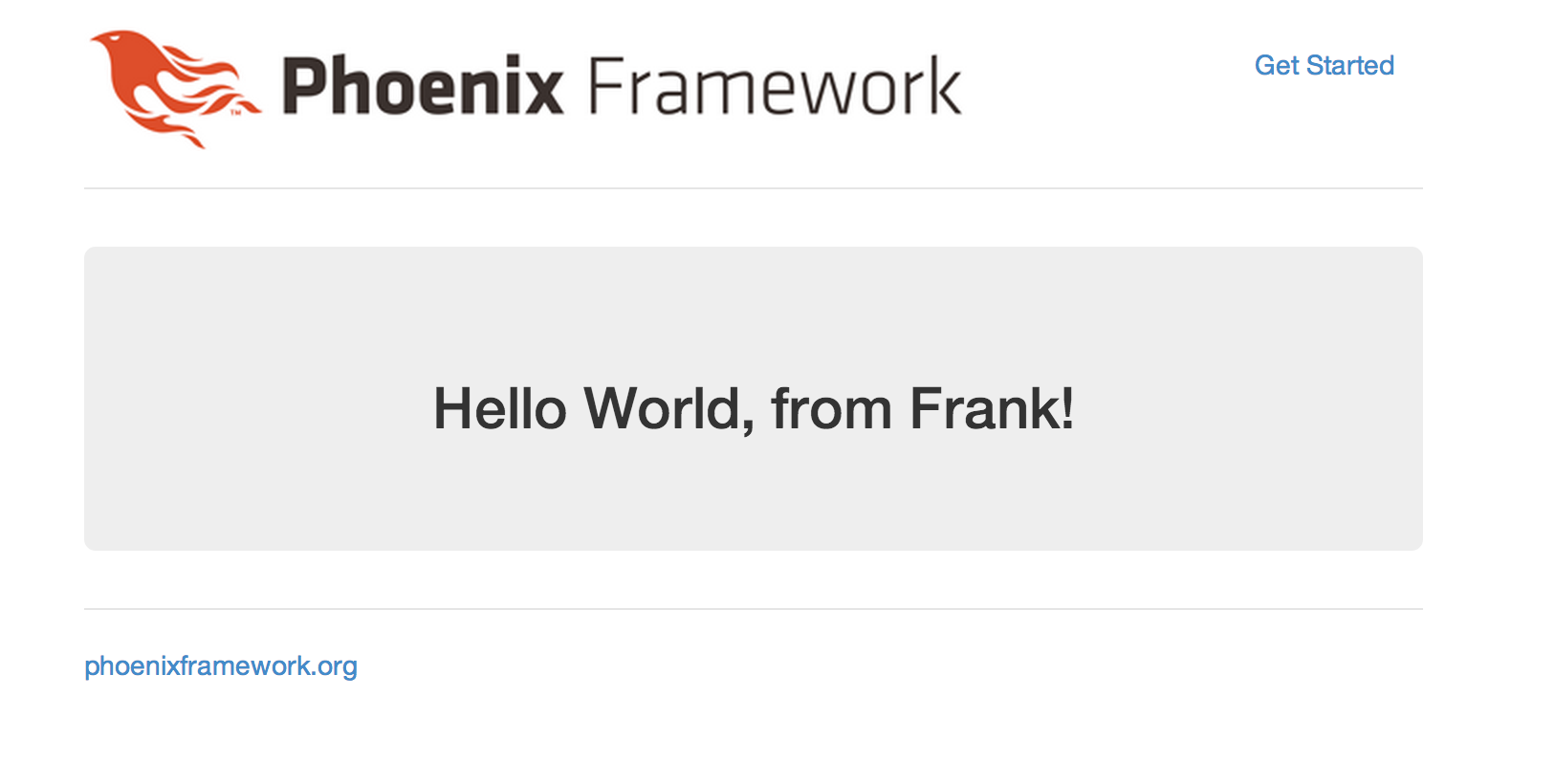

For example, if we point the browser at: http://localhost:4000/hello/Frank, the value of “:messenger” will be “Frank”.

A New Action

Requests to our new route will be handled by the HelloWeb.HelloController show action. We already have the controller at lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_controller.ex, so all we need to do is edit that file and add a show action to it. This time, we’ll need to keep one of the items in the map of params that gets passed into the action, so that we can pass it (the messenger) to the template. To do that, we add this show function to the controller:

def show(conn, %{"messenger" => messenger}) do

render conn, "show.html", messenger: messenger

endThere are a couple of things to notice here. We pattern match against the params passed into the show function so that the messenger variable will be bound to the value we put in the :messenger position in the URL. For example, if our URL is http://localhost:4000/hello/Frank, the messenger variable would be bound to Frank.

Within the body of the show action, we also pass a third argument into the render function, a key/value pair where :messenger is the key, and the messenger variable is passed as the value.

Note: If the body of the action needs access to the full map of parameters bound to the params variable in addition to the bound messenger variable, we could define

show/2like this:

def show(conn, %{"messenger" => messenger} = params) do

...

endIt’s good to remember that the keys to the params map will always be strings, and that the equals sign does not represent assignment, but is instead a pattern match assertion.

A New Template

For the last piece of this puzzle, we’ll need a new template. Since it is for the show action of the HelloController, it will go into the lib/hello_web/templates/hello directory and be called show.html.eex. It will look surprisingly like our index.html.eex template, except that we will need to display the name of our messenger.

To do that, we’ll use the special EEx tags for executing Elixir expressions - <%= %>. Notice that the initial tag has an equals sign like this: <%= . That means that any Elixir code that goes between those tags will be executed, and the resulting value will replace the tag. If the equals sign were missing, the code would still be executed, but the value would not appear on the page.

And this is what the template should look like:

<div class="jumbotron">

<h2>Hello World, from <%= @messenger %>!</h2>

</div>Our messenger appears as @messenger. In this case, this is not a module attribute. It is special bit of metaprogrammed syntax which stands in for assigns.messenger. The result is much nicer on the eyes and much easier to work with in a template.

We’re done. If you point your browser here: http://localhost:4000/hello/Frank, you should see a page that looks like this:

Play around a bit. Whatever you put after /hello/ will appear on the page as your messenger.