View Source Request life-cycle

Requirement: This guide expects that you have gone through the introductory guides and got a Phoenix application up and running.

The goal of this guide is to talk about Phoenix's request life-cycle. This guide will take a practical approach where we will learn by doing: we will add two new pages to our Phoenix project and comment on how the pieces fit together along the way.

Let's get on with our first new Phoenix page!

Adding a new page

When your browser accesses http://localhost:4000/, it sends a HTTP request to whatever service is running on that address, in this case our Phoenix application. The HTTP request is made of a verb and a path. For example, the following browser requests translate into:

| Browser address bar | Verb | Path |

|---|---|---|

| http://localhost:4000/ | GET | / |

| http://localhost:4000/hello | GET | /hello |

| http://localhost:4000/hello/world | GET | /hello/world |

There are other HTTP verbs. For example, submitting a form typically uses the POST verb.

Web applications typically handle requests by mapping each verb/path pair into a specific part of your application. This matching in Phoenix is done by the router. For example, we may map "/articles" to a portion of our application that shows all articles. Therefore, to add a new page, our first task is to add a new route.

A new route

The router maps unique HTTP verb/path pairs to controller/action pairs which will handle them. Controllers in Phoenix are simply Elixir modules. Actions are functions that are defined within these controllers.

Phoenix generates a router file for us in new applications at lib/hello_web/router.ex. This is where we will be working for this section.

The route for our "Welcome to Phoenix!" page from the previous Up And Running Guide looks like this.

get "/", PageController, :homeLet's digest what this route is telling us. Visiting http://localhost:4000/ issues an HTTP GET request to the root path. All requests like this will be handled by the home/2 function in the HelloWeb.PageController module defined in lib/hello_web/controllers/page_controller.ex.

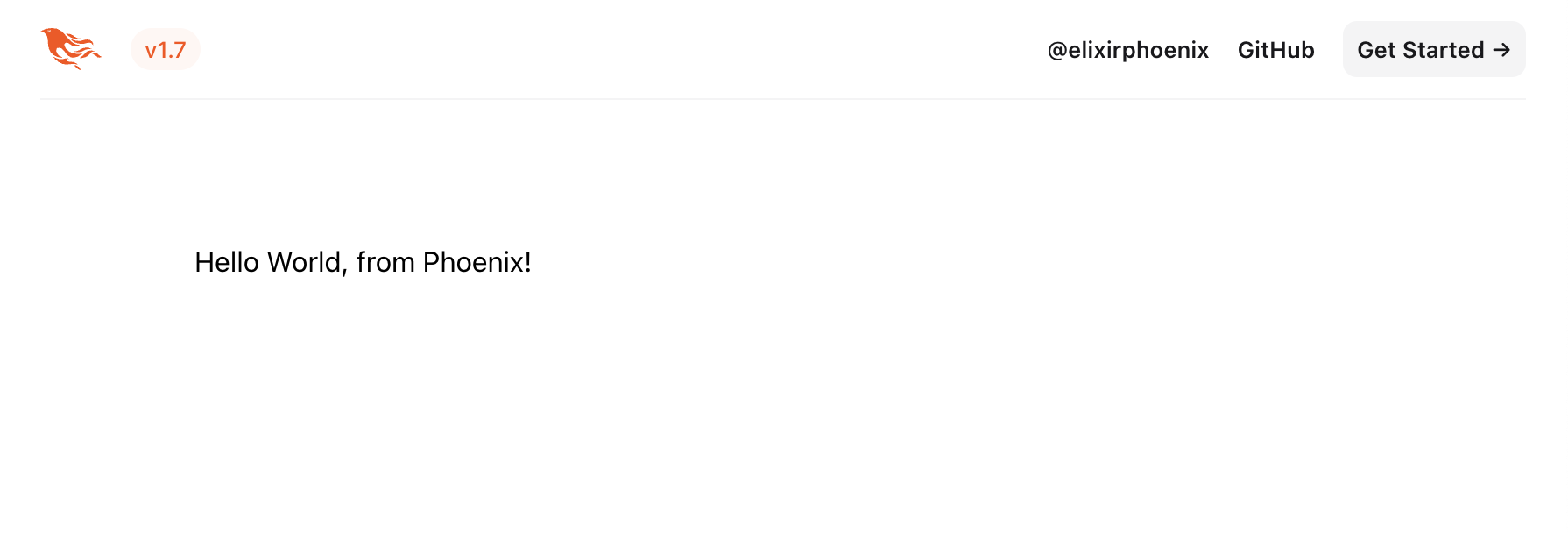

The page we are going to build will say "Hello World, from Phoenix!" when we point our browser to http://localhost:4000/hello.

The first thing we need to do is to create the page route for a new page. Let's open up lib/hello_web/router.ex in a text editor. For a brand new application, it looks like this:

defmodule HelloWeb.Router do

use HelloWeb, :router

pipeline :browser do

plug :accepts, ["html"]

plug :fetch_session

plug :fetch_live_flash

plug :put_root_layout, html: {HelloWeb.Layouts, :root}

plug :protect_from_forgery

plug :put_secure_browser_headers

end

pipeline :api do

plug :accepts, ["json"]

end

scope "/", HelloWeb do

pipe_through :browser

get "/", PageController, :home

end

# Other scopes may use custom stacks.

# scope "/api", HelloWeb do

# pipe_through :api

# end

# ...

endFor now, we'll ignore the pipelines and the use of scope here and just focus on adding a route. We will discuss those in the Routing guide.

Let's add a new route to the router that maps a GET request for /hello to the index action of a soon-to-be-created HelloWeb.HelloController inside the scope "/" do block of the router:

scope "/", HelloWeb do

pipe_through :browser

get "/", PageController, :home

get "/hello", HelloController, :index

endA new controller

Controllers are Elixir modules, and actions are Elixir functions defined in them. The purpose of actions is to gather the data and perform the tasks needed for rendering. Our route specifies that we need a HelloWeb.HelloController module with an index/2 function.

To make the index action happen, let's create a new lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_controller.ex file, and make it look like the following:

defmodule HelloWeb.HelloController do

use HelloWeb, :controller

def index(conn, _params) do

render(conn, :index)

end

endWe'll save a discussion of use HelloWeb, :controller for the Controllers guide. For now, let's focus on the index action.

All controller actions take two arguments. The first is conn, a struct which holds a ton of data about the request. The second is params, which are the request parameters. Here, we are not using params, and we avoid compiler warnings by prefixing it with _.

The core of this action is render(conn, :index). It tells Phoenix to render the index template. The modules responsible for rendering are called views. By default, Phoenix views are named after the controller (HelloController) and format (HTML in this case), so Phoenix is expecting a HelloWeb.HelloHTML to exist and define an index/1 function.

A new view

Phoenix views act as the presentation layer. For example, we expect the output of rendering index to be a complete HTML page. To make our lives easier, we often use templates for creating those HTML pages.

Let's create a new view. Create lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_html.ex and make it look like this:

defmodule HelloWeb.HelloHTML do

use HelloWeb, :html

endTo add templates to this view, we can define them as function components in the module or in separate files.

Let's start by defining a function component:

defmodule HelloWeb.HelloHTML do

use HelloWeb, :html

def index(assigns) do

~H"""

Hello!

"""

end

endWe defined a function that receives assigns as arguments and use the ~H sigil to put the contents we want to render. Inside the ~H sigil, we use a templating language called HEEx, which stands for "HTML+EEx". EEx is a library for embedding Elixir that ships as part of Elixir itself. "HTML+EEx" is a Phoenix extension of EEx that is HTML aware, with support for HTML validation, components, and automatic escaping of values. The latter protects you from security vulnerabilities like Cross-Site-Scripting with no extra work on your part.

A template file works in the same way. Function components are great for smaller templates and separate files are a good choice when you have a lot of markup or your functions start to feel unmanageable.

Let's give it a try by defining a template in its own file. First delete our def index(assigns) function from above and replace it with an embed_templates declaration:

defmodule HelloWeb.HelloHTML do

use HelloWeb, :html

embed_templates "hello_html/*"

endHere we are telling Phoenix.Component to embed all .heex templates found in the sibling hello_html directory into our module as function definitions.

Next, we need to add files to the lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_html directory.

Note the controller name (HelloController), the view name (HelloHTML), and the template directory (hello_html) all follow the same naming convention and are named after each other. They are also collocated together in the directory tree:

Note: We can rename the

hello_htmldirectory to whatever we want and put it in a subdirectory oflib/hello_web/controllers, as long as we update theembed_templatessetting accordingly. However, it's best to keep the same naming convention to prevent any confusion.

lib/hello_web

├── controllers

│ ├── hello_controller.ex

│ ├── hello_html.ex

│ ├── hello_html

| ├── index.html.heexA template file has the following structure: NAME.FORMAT.TEMPLATING_LANGUAGE. In our case, let's create an index.html.heex file at lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_html/index.html.heex:

<section>

<h2>Hello World, from Phoenix!</h2>

</section>Template files are compiled into the module as function components themselves, there is no runtime or performance difference between the two styles.

Now that we've got the route, controller, view, and template, we should be able to point our browsers at http://localhost:4000/hello and see our greeting from Phoenix! (In case you stopped the server along the way, the task to restart it is mix phx.server.)

There are a couple of interesting things to notice about what we just did. We didn't need to stop and restart the server while we made these changes. Yes, Phoenix has hot code reloading! Also, even though our index.html.heex file consists of only a single section tag, the page we get is a full HTML document. Our index template is actually rendered into layouts: first it renders lib/hello_web/components/layouts/root.html.heex which renders lib/hello_web/components/layouts/app.html.heex which finally includes our contents. If you open those files, you'll see a line that looks like this at the bottom:

<%= @inner_content %>Which injects our template into the layout before the HTML is sent off to the browser. We will talk more about layouts in the Controllers guide.

A note on hot code reloading: Some editors with their automatic linters may prevent hot code reloading from working. If it's not working for you, please see the discussion in this issue.

From endpoint to views

As we built our first page, we could start to understand how the request life-cycle is put together. Now let's take a more holistic look at it.

All HTTP requests start in our application endpoint. You can find it as a module named HelloWeb.Endpoint in lib/hello_web/endpoint.ex. Once you open up the endpoint file, you will see that, similar to the router, the endpoint has many calls to plug. Plug is a library and a specification for stitching web applications together. It is an essential part of how Phoenix handles requests and we will discuss it in detail in the Plug guide coming next.

For now, it suffices to say that each plug defines a slice of request processing. In the endpoint you will find a skeleton roughly like this:

defmodule HelloWeb.Endpoint do

use Phoenix.Endpoint, otp_app: :hello

plug Plug.Static, ...

plug Plug.RequestId

plug Plug.Telemetry, ...

plug Plug.Parsers, ...

plug Plug.MethodOverride

plug Plug.Head

plug Plug.Session, ...

plug HelloWeb.Router

endEach of these plugs have a specific responsibility that we will learn later. The last plug is precisely the HelloWeb.Router module. This allows the endpoint to delegate all further request processing to the router. As we now know, its main responsibility is to map verb/path pairs to controllers. The controller then tells a view to render a template.

At this moment, you may be thinking this can be a lot of steps to simply render a page. However, as our application grows in complexity, we will see that each layer serves a distinct purpose:

endpoint (

Phoenix.Endpoint) - the endpoint contains the common and initial path that all requests go through. If you want something to happen on all requests, it goes to the endpoint.router (

Phoenix.Router) - the router is responsible for dispatching verb/path to controllers. The router also allows us to scope functionality. For example, some pages in your application may require user authentication, others may not.controller (

Phoenix.Controller) - the job of the controller is to retrieve request information, talk to your business domain, and prepare data for the presentation layer.view - the view handles the structured data from the controller and converts it to a presentation to be shown to users. Views are often named after the content format they are rendering.

Let's do a quick recap and how the last three components work together by adding another page.

Another new page

Let's add just a little complexity to our application. We're going to add a new page that will recognize a piece of the URL, label it as a "messenger" and pass it through the controller into the template so our messenger can say hello.

As we did last time, the first thing we'll do is create a new route.

Another new route

For this exercise, we're going to reuse HelloController created at the previous step and add a new show action. We'll add a line just below our last route, like this:

scope "/", HelloWeb do

pipe_through :browser

get "/", PageController, :home

get "/hello", HelloController, :index

get "/hello/:messenger", HelloController, :show

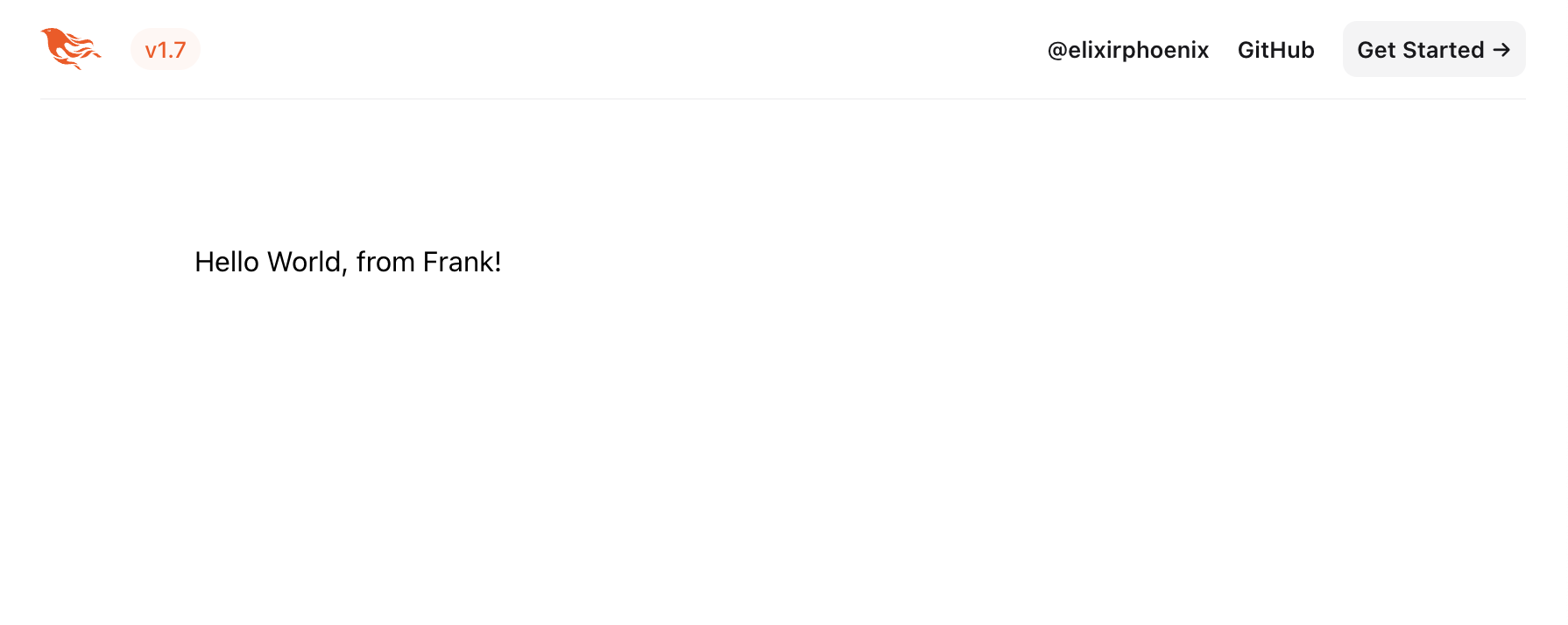

endNotice that we use the :messenger syntax in the path. Phoenix will take whatever value that appears in that position in the URL and convert it into a parameter. For example, if we point the browser at: http://localhost:4000/hello/Frank, the value of "messenger" will be "Frank".

Another new action

Requests to our new route will be handled by the HelloWeb.HelloController show action. We already have the controller at lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_controller.ex, so all we need to do is edit that controller and add a show action to it. This time, we'll need to extract the messenger from the parameters so that we can pass it (the messenger) to the template. To do that, we add this show function to the controller:

def show(conn, %{"messenger" => messenger}) do

render(conn, :show, messenger: messenger)

endWithin the body of the show action, we also pass a third argument to the render function, a key-value pair where :messenger is the key, and the messenger variable is passed as the value.

If the body of the action needs access to the full map of parameters bound to the params variable, in addition to the bound messenger variable, we could define show/2 like this:

def show(conn, %{"messenger" => messenger} = params) do

...

endIt's good to remember that the keys of the params map will always be strings, and that the equals sign does not represent assignment, but is instead a pattern match assertion.

Another new template

For the last piece of this puzzle, we'll need a new template. Since it is for the show action of HelloController, it will go into the lib/hello_web/controllers/hello_html directory and be called show.html.heex. It will look surprisingly like our index.html.heex template, except that we will need to display the name of our messenger.

To do that, we'll use the special HEEx tags for executing Elixir expressions: <%= %>. Notice that the initial tag has an equals sign like this: <%= . That means that any Elixir code that goes between those tags will be executed, and the resulting value will replace the tag in the HTML output. If the equals sign were missing, the code would still be executed, but the value would not appear on the page.

Remember our templates are written in HEEx (HTML+EEx). HEEx is a superset of EEx which is why it shares the <%= %> syntax.

And this is what the template should look like:

<section>

<h2>Hello World, from <%= @messenger %>!</h2>

</section>Our messenger appears as @messenger.

The values we passed to the view from the controller are collectively called our "assigns". We could access our messenger value via assigns.messenger but through some metaprogramming, Phoenix gives us the much cleaner @ syntax for use in templates.

We're done. If you point your browser to http://localhost:4000/hello/Frank, you should see a page that looks like this:

Play around a bit. Whatever you put after /hello/ will appear on the page as your messenger.